Goldenhand is a welcome return to Garth Nix’s Old Kingdom universe, but it unfortunately feels, overall, a bit half-baked. It’s an enjoyable read if one doesn’t think too hard about it, but the truth is that Goldenhand is problematic in numerous ways that detract from the joy of revisiting such a well-loved fantasy world.

Goldenhand is a welcome return to Garth Nix’s Old Kingdom universe, but it unfortunately feels, overall, a bit half-baked. It’s an enjoyable read if one doesn’t think too hard about it, but the truth is that Goldenhand is problematic in numerous ways that detract from the joy of revisiting such a well-loved fantasy world.

Goldenhand is a direct continuation of Lirael’s story following the events of Abhorsen and picking up about a year or so later. It also incorporates events from the novella The Creature in the Case, which continued the story of Nicholas Sayre after he returns to Ancelstierre at the end of Abhorsen. Lirael has been hard at work learning in her role as Abhorsen-in-waiting to her sister, Sabriel, and she’s given the chance to take on more responsibility when Sabriel and Touchstone go on their first vacation in twenty years. Meanwhile, after accidentally freeing and empowering a dangerous free magic creature, Nick is on his way back towards the Old Kingdom in pursuit of it. Meanwhile, Chlorr is still stirring up trouble in the north, and it turns out there’s a whole previously unmentioned group of people that are being used for Chlorr’s nefarious ends. There’s a lot going on, at least ostensibly. Perhaps the biggest problem with Goldenhand is that, despite the ambitious worldbuilding and great number of things happening, none of it particularly works.

It was interesting at first to be introduced to Ferin and her people, but with only Ferin as a point of view for that part of the world and no sense of what normal life is like for the tribes, there’s ultimately very little to learn about these new people and their culture. Ferin herself has a very specific and non-normative experience within that culture—she was raised to be basically a sacrifice, sequestered from the rest of the tribe and denied even the humanity of a proper name (“Ferin” is from a childish mispronunciation of “Offering”)—and she’s the only one of her people the reader meets directly. The rest are faceless villains and obstacles for our heroes to overcome, and there’s no real sense of who these people are and how they normally fit into the regular fabric of the Old Kingdom. This diminishes the reader’s investment in Ferin’s history and struggle, and it’s not helped along by Ferin’s extremely practical nature. She’s so pragmatic about everything that happens to her that it ends up feeling as if she isn’t affected very much by anything she goes through. This would be frustrating in a minor character, but Ferin is a point of view character for fully half of this book, and it’s extremely difficult to become really immersed in a perspective that is so poorly socialized and without enough context for understanding why and how she’s the way she is. Ferin is a weird character, and not in a good way. Rather, she takes up a lot of page space without ever being compelling enough to be a proper balance or complement to Lirael, who we already know from previous books.

Sadly, Lirael, too, is a lot less interesting this time around. Lirael and Abhorsen were heavily focused on Lirael’s journey to discovering her own identity and finding her place in the world, and there was a clear and well-executed character arc as she came of age. Goldenhand gives us a Lirael who is much more confident and self-assured to start with, which isn’t necessarily a bad thing, but this Lirael doesn’t have nearly so much to learn or so far to travel, for all that she goes fully from one end of the Kingdom to the other. Some attention is paid both to Lirael’s lost hand and her grief over her missing friend, the Disreputable Dog, but neither of these things are given the weight they ought to have. Indeed, Prince Sameth has already built a magical gold hand for Lirael by the start of the book, which effectively erases her disability. Most of Lirael’s thoughts about her hand are marveling at how functional the magical prosthetic is rather than lamenting the loss of the real hand. Similarly, Lirael does at times miss the Dog, but with everything else going on there’s not much time for truly exploring her feelings of sadness and loss. Instead, Lirael’s primary arc in this book is a romantic one, mostly centered around her growing feelings for Nick and her relationship with him. While Lirael’s final dealing with Chlorr/Clariel seems intended to be a climax for the story, it happens quickly and the novel is then ended rather abruptly, which prevents the event from having much emotional weight.

This lack of impact is, frankly, characteristic of Goldenhand. Erasing Lirael’s disability and glossing over her grieving process in favor of focusing on her burgeoning relationship with a man she barely knows (and who doesn’t get much development of his own, by the way) makes for a very slight novel. Both that romance and Lirael’s quest to stop Chlorr once and for all rely far too much on previous books in the series to generate what interest they do hold. If you haven’t read Lirael, Abhorsen, and Clariel (and preferably The Creature in the Case as well), you’re likely to find yourself more than a little at sea in Goldenhand. Goldenhand is not an entry point into the Old Kingdom for new readers; it’s a book for superfans who will consume anything they can get in this setting without being too picky about things making sense. This overall effect might have been counteracted if Ferin’s story was stronger, but Ferin’s goals and purpose are never quite clear; she is trying to do something to save her people I guess, but most of her chapters are taken up by an aimless chase that never manages to feel dangerous or high stakes enough to justify its existence. Instead of acting as a powerful new addition to the series, Ferin’s story functions mostly as a rather dull and uninspired distraction in what might otherwise have been a decent piece of fan service.

While Garth Nix does a lot of work here to expand the world of the Old Kingdom and provide more theoretically fertile ground for, presumably, future sequels, Goldenhand is plagued with enough craft problems and various missteps that it’s hard to get very excited to learn what comes next. Unless it involves queer Ellimere (I mean, come on—everyone else has been paired off heterosexually now) and lots of Mogget (there was not nearly enough Mogget in this book), I can’t say I’m very interested.

If you want to read ghost stories, read something besides this book. Certainly, Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places contains ghost stories, but if you’re looking for titillating tales of terror for an autumn evening, you won’t find it here. Colin Dickey’s Ghostland isn’t about scaring its readers; rather, it’s a smartly eclectic work of history that looks to examine the whole ghost story phenomenon. Why do we tell ghost stories? Whose stories get told? What do these stories tell us about the places and people with which they’re associated? What do these stories say about the ways in which we, as a society, interact with death and with history? How do ghost stories help us connect with our past—and in what ways do they help us disconnect from aspects of the past that are unpleasant? If Dickey isn’t entirely successful in answering all these questions, he’s nonetheless crafted an engaging work of popular history that does a great job of introducing these ideas to the reader and encouraging further inquiry.

If you want to read ghost stories, read something besides this book. Certainly, Ghostland: An American History in Haunted Places contains ghost stories, but if you’re looking for titillating tales of terror for an autumn evening, you won’t find it here. Colin Dickey’s Ghostland isn’t about scaring its readers; rather, it’s a smartly eclectic work of history that looks to examine the whole ghost story phenomenon. Why do we tell ghost stories? Whose stories get told? What do these stories tell us about the places and people with which they’re associated? What do these stories say about the ways in which we, as a society, interact with death and with history? How do ghost stories help us connect with our past—and in what ways do they help us disconnect from aspects of the past that are unpleasant? If Dickey isn’t entirely successful in answering all these questions, he’s nonetheless crafted an engaging work of popular history that does a great job of introducing these ideas to the reader and encouraging further inquiry.

I read all of Tor.com’s novellas, which is a good thing because I otherwise might have missed out on this gem by S.B. Divya. I would never have picked up a story about a cyborg endurance race on my own, but I’m glad I read this one. Runtime is a marvel of world building and character portraiture wrapped around a perfectly executed straightforward plot and just the right amount of smart-but-not-overbearing social commentary. It’s a near-perfect use of the novella length, and I cannot wait to see what S.B. Divya does next.

I read all of Tor.com’s novellas, which is a good thing because I otherwise might have missed out on this gem by S.B. Divya. I would never have picked up a story about a cyborg endurance race on my own, but I’m glad I read this one. Runtime is a marvel of world building and character portraiture wrapped around a perfectly executed straightforward plot and just the right amount of smart-but-not-overbearing social commentary. It’s a near-perfect use of the novella length, and I cannot wait to see what S.B. Divya does next.

I didn’t hate Guy Haley’s first Dreaming Cities novella, The Emperor’s Railroad, though it wasn’t one of my favorite reads of the year so far. Nonetheless, I was intrigued enough to read this second installment of the series. The Ghoul King seemed to promise more action and a female character with something to do besides die for male character development, and I was hoping to see Haley dig a little deeper into some of the potentially very cool world building of his post-apocalyptic landscape. Sadly, I found myself disappointed on all counts with this book, and this is another series that I’m very unlikely to continue with.

I didn’t hate Guy Haley’s first Dreaming Cities novella, The Emperor’s Railroad, though it wasn’t one of my favorite reads of the year so far. Nonetheless, I was intrigued enough to read this second installment of the series. The Ghoul King seemed to promise more action and a female character with something to do besides die for male character development, and I was hoping to see Haley dig a little deeper into some of the potentially very cool world building of his post-apocalyptic landscape. Sadly, I found myself disappointed on all counts with this book, and this is another series that I’m very unlikely to continue with.

I won’t be reading anything else by Andy Remic. I didn’t care for most of his first Tor.com novella, A Song for No Man’s Land, but it got interesting right at the end. Unfortunately, Return of Souls doesn’t deliver on what little promise its predecessor held. Instead, it doubles down on everything I didn’t like about the first book in this planned trilogy and adds a heaping dose of blatant misogyny that makes it a deeply unpleasant read.

I won’t be reading anything else by Andy Remic. I didn’t care for most of his first Tor.com novella, A Song for No Man’s Land, but it got interesting right at the end. Unfortunately, Return of Souls doesn’t deliver on what little promise its predecessor held. Instead, it doubles down on everything I didn’t like about the first book in this planned trilogy and adds a heaping dose of blatant misogyny that makes it a deeply unpleasant read.

I adored Fran Wilde’s debut novel, Updraft, so I was thrilled when I learned she had written one of Tor.com’s novellas. The Jewel and Her Lapidary was one of my most anticipated books for the first half of 2016, so imagine my surprise and dismay when I turned out to just not care for it very much.

I adored Fran Wilde’s debut novel, Updraft, so I was thrilled when I learned she had written one of Tor.com’s novellas. The Jewel and Her Lapidary was one of my most anticipated books for the first half of 2016, so imagine my surprise and dismay when I turned out to just not care for it very much.

I really liked A Court of Thorns and Roses when I read it last year, so I was looking forward to A Court of Mist and Fury quite a bit. After how neatly ACOTAR seemed to wrap things up, especially with the romance between Feyre and Tamlin, I wasn’t entirely certain where ACOMAF was going to take things, and I was honestly very concerned that it was going to veer into tiresome love triangle territory. I needn’t have worried. ACOMAF wasn’t what I thought it would be, but it was engaging, exciting, and sexy enough that I read it in a single day.

I really liked A Court of Thorns and Roses when I read it last year, so I was looking forward to A Court of Mist and Fury quite a bit. After how neatly ACOTAR seemed to wrap things up, especially with the romance between Feyre and Tamlin, I wasn’t entirely certain where ACOMAF was going to take things, and I was honestly very concerned that it was going to veer into tiresome love triangle territory. I needn’t have worried. ACOMAF wasn’t what I thought it would be, but it was engaging, exciting, and sexy enough that I read it in a single day.

Ada Palmer’s Too Like the Lightning is a tremendously, gloriously wonderful book that seems like an obvious contender for all of the genre awards next year. It’s a remarkably original, refreshingly optimistic (but not cloyingly so), and deeply challenging read that demands the reader’s full attention. It’s a novel that is difficult at times, but it’s very much worth taking the time—and it may take quite a while—to work through.

Ada Palmer’s Too Like the Lightning is a tremendously, gloriously wonderful book that seems like an obvious contender for all of the genre awards next year. It’s a remarkably original, refreshingly optimistic (but not cloyingly so), and deeply challenging read that demands the reader’s full attention. It’s a novel that is difficult at times, but it’s very much worth taking the time—and it may take quite a while—to work through.

It would have been useful to know in advance that Central Station is a novel that was cobbled together from a collection of related short stories. While there is much to love about the finished product, it nonetheless has a somewhat disjointed feel to it that makes it somewhat difficult to fully appreciate the novel’s strong points. It’s not incoherent, exactly, just slightly garbled in execution, which is too bad because Central Station is otherwise a gorgeously imagined, smartly written, ambitious work of thoughtful futurism.

It would have been useful to know in advance that Central Station is a novel that was cobbled together from a collection of related short stories. While there is much to love about the finished product, it nonetheless has a somewhat disjointed feel to it that makes it somewhat difficult to fully appreciate the novel’s strong points. It’s not incoherent, exactly, just slightly garbled in execution, which is too bad because Central Station is otherwise a gorgeously imagined, smartly written, ambitious work of thoughtful futurism.

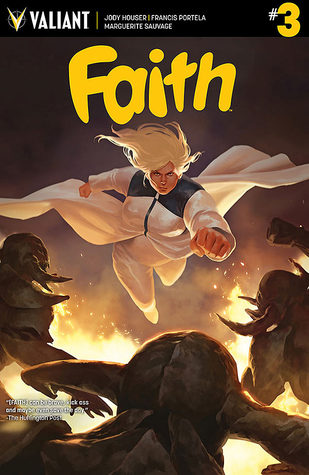

Faith’s geek status is a major part of her relatability as a character, and it also makes the comic a bit of interesting meta commentary on comics, fandom, and geek culture in general. After some personal upheaval, Faith hangs up her cape (theoretically, anyway) and moves to Los Angeles to be a pop culture blogger before she’s forced by circumstance to put her costume back on and get back into the superhero game. It’s not unusual for superheroes to have secret identities, and even Faith’s job in media isn’t unusual, but her particular situation is uniquely and distinctively of the early twenty-first century. I have a feeling that, years from now, this is going to date this book, and it’s possible that it won’t hold up well to the test of time, but it’s a specificity that adds to the authenticity of Faith’s earnest storytelling. You can tell, both in the art and the smart, funny writing, that the people behind this book really care about geek culture and have a good amount of inside knowledge.

Faith’s geek status is a major part of her relatability as a character, and it also makes the comic a bit of interesting meta commentary on comics, fandom, and geek culture in general. After some personal upheaval, Faith hangs up her cape (theoretically, anyway) and moves to Los Angeles to be a pop culture blogger before she’s forced by circumstance to put her costume back on and get back into the superhero game. It’s not unusual for superheroes to have secret identities, and even Faith’s job in media isn’t unusual, but her particular situation is uniquely and distinctively of the early twenty-first century. I have a feeling that, years from now, this is going to date this book, and it’s possible that it won’t hold up well to the test of time, but it’s a specificity that adds to the authenticity of Faith’s earnest storytelling. You can tell, both in the art and the smart, funny writing, that the people behind this book really care about geek culture and have a good amount of inside knowledge. led to me putting off reading the book for longer than I otherwise might have.

led to me putting off reading the book for longer than I otherwise might have.