Confession time: I’ve not read very much classic science fiction. As a kid, I was always more into dragons and wizards than space ships and aliens, and as an adult I find I’m just not often interested in reading books that are older than I am. Still, Arthur C. Clarke is one of the greats, Childhood’s End is one of my partner’s favorite books, and it’s getting a miniseries on SyFy later this year, so I felt like it was time to read this one.

Confession time: I’ve not read very much classic science fiction. As a kid, I was always more into dragons and wizards than space ships and aliens, and as an adult I find I’m just not often interested in reading books that are older than I am. Still, Arthur C. Clarke is one of the greats, Childhood’s End is one of my partner’s favorite books, and it’s getting a miniseries on SyFy later this year, so I felt like it was time to read this one.

I’m glad I did, although it was many of the things that I expected. It’s somewhat simplistic, the characters are rather shallow, and its politics are dated at best. I can see why Childhood’s End is a classic, though. It’s an excellent novel, a fairly quick read, and has some ideas that stand the test of time really well. This makes it an all around worthwhile read for anyone who really loves science fiction.

So, to start with, I hadn’t realized exactly how old this book was. When I started it, I was thinking it was from the 1960s, but it was actually published in 1953. This explains some of the weirdness early in the book, which almost reads as if it’s about the Cold War and the Space Race, but which couldn’t have been. While 1953 was early in the Cold War, the Space Race wouldn’t start for another two years, although apparently in 1953 Clarke didn’t see humanity making it to space before the mid-70s.

Although I don’t read much sci-fi from this period, I always find it entertaining to see what these older writers thought the future would look like then. The flip side of this, though, is that sometimes they were just dead wrong. For example, in a kind of throwaway mention early in the book, Clarke describes white people in South Africa as an oppressed minority by 1975, and I would love to go back in time and pick his brain about what made him think that. By 1953, South Africa was already five years into the apartheid that wouldn’t end until 1994.

Another interesting, if expected, thing about this book and Clarke’s vision of the future is that, like many of the men who wrote science fiction in the mid 20th century, Clarke seems perfectly capable of imagining a future in which humanity sheds all its puritanical sexual mores, but he didn’t imagine a future where women’s liberation happened. There are only a couple of women in Childhood’s End, and they are barely even characters at all. Maia Boyce’s single trait is being really beautiful. Jean Morrel is somewhat more important, but she’s basically a sort of 1950s housewife whose husband can’t be bothered to be “in love with” until the world is literally ending. Apparently post-1990 publications of the book have made one of the astronauts in the first chapter a woman, but not the copy of the book that I read.

Regarding race, Clarke’s dream of the future is even more frustrating. Like many sort of clueless white dudes, he seemed to think that racial slurs would survive into a post-racism world but that they would somehow just kind of magically lose their negative connotations. Which is just not how language works, and betrays a really weird fantasy, in my opinion, of being able to still be just as racist as ever except no one complains about it anymore.

At the same time, though, perhaps the most important character in Childhood’s End is a black man, Jan Rodricks, who is the only human to see the Overlords’ home world and survives to chronicle the last days of the planet Earth. Jan is written in a way that is non-stereotypical, and by the end of the book one definitely gets the feeling that Jan comes closest of any of the characters in Childhood’s End to being Arthur C. Clarke’s ideal of manhood. While the author may have some ideas about race and gender that seem archaic over sixty years later, he was certainly progressive for his time.

The thing about Childhood’s End, though, is that it’s really not a character-driven book. It doesn’t even have a particularly strong plot. Very little actually happens, and if one were to consider the story Clarke tells in this book against the whole backdrop of time, his portrait of humanity is akin to taking a snapshot of a 90-year-old person just moments before they die. Childhood’s End is a book about ideas, and the characters and story are almost incidental to the big things that Clarke wanted to think about in 1953.

In Childhood’s End, Clarke imagines a utopia, then the dystopia inside it. He dreams up a perfect world, then he picks it apart, and then he tells us that none of it matters anyway. I can’t tell if Childhood’s End is profoundly optimistic about humanity or if it’s deeply pessimistic, but it’s definitely given me some things to think about.

One thing I will say unequivocally, though, is that SyFy is definitely going to screw up the adaptation of it. Which is sad, because Charles Dance will be a perfect Karellan and I hate to see him wasted on whatever the nonsense is that SyFy is going to air with the same title as this lovely book.

Spindle is a charming little self-published title by Tasmanian author

Spindle is a charming little self-published title by Tasmanian author

Shadowshaper seems to be most often compared to Cassandra Clare’s Mortal Instruments, but it’s a terrible comparison. In fact, there is no comparison to be made that isn’t entirely superficial. Shadowshaper isn’t a flawless piece of work, but it’s not a mess of derivative, hackneyed tropes like the Mortal Instruments series was, either.

Shadowshaper seems to be most often compared to Cassandra Clare’s Mortal Instruments, but it’s a terrible comparison. In fact, there is no comparison to be made that isn’t entirely superficial. Shadowshaper isn’t a flawless piece of work, but it’s not a mess of derivative, hackneyed tropes like the Mortal Instruments series was, either.

I’m not sure that most people would agree with me that The Philosopher Kings is a fun read, but I enjoyed it at least as well as I did its predecessor, The Just City. After the rather abrupt and somewhat shocking ending of the previous book, I couldn’t wait to see what happened next.

I’m not sure that most people would agree with me that The Philosopher Kings is a fun read, but I enjoyed it at least as well as I did its predecessor, The Just City. After the rather abrupt and somewhat shocking ending of the previous book, I couldn’t wait to see what happened next.

The Heart Goes Last by Margaret Atwood

The Heart Goes Last by Margaret Atwood

Shadowshaper by Daniel José Older

Shadowshaper by Daniel José Older

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet by Becky Chambers

The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet by Becky Chambers The Dinosaur Lords by Victor Milán

The Dinosaur Lords by Victor Milán The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin

The Fifth Season by N.K. Jemisin

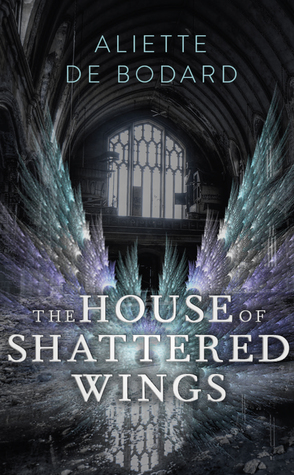

The House of Shattered Wings by Aliette de Bodard

The House of Shattered Wings by Aliette de Bodard