**Trigger Warning: Discussion of Rape**

**Trigger Warning: Discussion of Rape**

The Dinosaur Lords is being sold as “a cross between Jurassic Park and Game of Thrones,” which sounds pretty rad. I like dinosaurs, and I like medieval fantasy so, even though Victor Milán’s previous work was (apparently) libertarian sci-fi (which would normally be a dealbreaker for me), I decided to give this book a try. It helped that it’s got an absolutely gorgeous (if absurd) cover and that the black and white interior illustrations are similarly lovely. This is also a novel that has been getting an enormous amount of buzz. Its got a quote on the cover from George R.R. Martin, the concept for the book is fun, and the author has done a ton of guest blogging and self-promotion in addition to heavy promotion for it at Tor.

Unfortunately, the concept, packaging and advertising for the book are the best things about it. The Dinosaur Lords is by far the biggest reading disappointment I’ve had this year. To be fair, I probably should have known better than to give this book and its author the benefit of the doubt, but I really, really wanted to read about knights riding dinosaurs. And there was supposed to be an allosaurus as a point of view character!

So (spoiler alert!) the “allosaurus as a POV character” thing was vastly exaggerated in the promotion of the book. In reality, Shiraa’s point of view amounts to just a handful of paragraphs near the beginning and end of the novel. Also, it turns out that dinosaur POVs are boring as shit and even these few paragraphs are more than the book needed of that experiment. This is basically the least of The Dinosaur Lords‘ sins, though.

To be honest, I’m not sure what makes me most angry about this book: its rank misogyny or that the misogyny doesn’t even make much sense. Like, Milán really has to bend over backwards with his storytelling and world building to shoehorn his particular brand of woman-hating into the book. It would end up being laughably bad if it wasn’t too busy alternating between offensively nonsensical and viscerally unpleasant.

The book opens with an author’s note clarifying that Paradise isn’t/wasn’t/will never be earth, which is weird; Milán wanted to make it really clear that this wasn’t a book supporting young Earth creationism. It comes off as really oddly defensive about something that I kind of feel like no one actually cares about, and it’s a, frankly, bizarre way to start a novel. Milán actually touches on this in a guest post over at the B&N Sci-Fi & Fantasy Blog, where he brags at some length about his lazy world building. Apparently, he just sort of chose ideas that he thought sounded “cool” and tossed them all together along with some ideas calculated to increase book sales.

I won’t say that the world building in The Dinosaur Lords is completely atrocious because it’s not. Sure, Milán has shamelessly cribbed from Anne McCaffrey’s Pern, but he actually has some good ideas of his own. Unfortunately, it all just becomes completely bogged down in absurd contradictions that just get worse and worse as the book goes on.

So, Paradise is, from what I can gather, a cultivated world akin to Pern where humans presumably traveled some several hundred years in the past, seeded the planet with plants and animal life to make it suitable for human habitation, set up a kind of inexplicably feudal society, and decided (also inexplicably, because it’s a terrible idea) to keep the whole thing in place by passing down their plans and rules in the form of kind of sacred texts that explain the world and tell people how things are supposed to be run. All of this I could forgive, even though there’s no reason I can think of that any spacefaring species would be attempting a form of government/economy as inefficient and iniquitous as feudalism.

The thing is, The Dinosaur Lords isn’t a story about a scrappy group of underdogs fighting to overthrow an oppressive regime. It’s not even like Game of Thrones, where there are a wide variety of point of view characters who largely exists in the margins of their society and whose stories are interesting studies of complex individuals. Nope. The Dinosaur Lords instead expects us to spend four hundred-odd pages inside the heads of the oppressive regime, with POV characters (besides the allosaurus) including a self-absorbed yes man of a knight, a naive and sheltered imperial princess, a sort of mercenary lord who has lost his lands and army, and a supposed everyman character who spends much of his time thinking about how admirable the right kind of nobility are. Of these characters, the princess is the most interesting, but most of the problems I have with this book come from it’s depictions of female characters.

Paradise is a world that truly is wonderful for its inhabitants. People live for hundreds of years, there’s almost no disease, and any injury that doesn’t outright kill someone will heal in a matter of days. However, women still die in childbirth, I guess because the author doesn’t actually know much about childbirth. Also because it was convenient for him to have Princess Melodia’s mother dead so he wouldn’t have to write about her. So, that’s a thing in this book. Admittedly, I have a special hatred for the Missing Mom trope, but it’s used in an especially lazy manner here, where by the rules of the fantasy world death in childbirth ought to be vanishingly rare.

The way that gender and sexuality is portrayed in the book is just bizarre, in general. Paradise is a world where nudity is no big deal, but women can apparently still feel naked and vulnerable because of their gender. It’s a world where women are sexually “liberated” enough that they can freely have sex with men and each other, but where rape culture continues to thrive and rape is relatively common and no woman is safe from it. Women in Paradise can choose their sexual partners (unless they’re raped), but they still have to get their father’s permission to marry who they want. It’s a world where homosexuality is normalized to the point that one of the most elite military groups in the world is primarily made up of gay and bisexual men but where “boy-fucker” is still an insult. It’s a world where we’re told that women can be fighters as well as men, but with the condescending caveats that to actually participate in warfare is “beneath a noblewoman’s station” and that they have to learn fighting styles that accommodate “woman’s relative lack of muscle.” Also, I think that there is precisely one named female fighter in the book, even though it’s implied that there are many.

Over and over again, the book tells us that women are equal to men but shows that this isn’t really the case. In Paradise, women are decidedly subordinate to men in a disappointingly familiar patriarchal landscape, and they are similarly marginalized in the fabric of the novel. The first female character we see in the book is a random old lady who gets killed while looting bodies after a battle, and Melodia is the only female point of view character besides the allosaurus. It seems promising early on that Melodia is surrounded by so many other female characters, but her ladies are largely a pack of unpleasant catty stereotypes. Even to the degree that they are likable, Melodia and her ladies read like a male fantasy of the way groups of women interact together, and there is nothing particularly real or relatable about them whatsoever.

Perhaps the most disappointing thing about the treatment of women in The Dinosaur Lords is the prevalence of rape. I find it disgusting how ubiquitous rape still is as a cheap plot device and an easy way for authors to add some grimdark seasoning to their settings, and rape is used in exceptionally sickening ways in this book. The worst, though, is Melodia’s fairly graphic rape at the hands of a scheming courtier, and what makes this the worst is that the way it’s written is more like a sex scene in a romance novel than a rape.

The set up for the rape starts about two thirds through the book when Melodia spends an evening dancing with the guy who will eventually rape her. She seems somewhat attracted to him, but then the magic of the evening wears off and she realizes that she’s still devoted to her absent fiance, but not before having to be rescued from this dude because he almost rapes her right then. We’re then treated to an absolutely vile discussion between the rapist and another dude, where they talk about what a cock-teasing bitch Melodia is in one of the grossest scenes I’ve read in any book in a long time–made even more sickening because on some level the reader is supposed to identify and sympathize with the rapist guy.

I about quit reading right then because I was so certain that Melodia was going to be raped by the end of the book, but I kept reading against my better judgment. And there was no rape for a while. Just when I’d been thinking that maybe it wasn’t going to happen after all, though, it did. Melodia is imprisoned and raped by the guy that it was heavily telegraphed she was going to be raped by. The thing is, Milán is so coy about it. The way he writes the actual rape manages to be graphic enough to be so unsettling that I almost vomited, but it also reads like the penultimate sex scene of a romance novel, complete with the fade to black that is normally intended to allow the reader to use their imagination.

After the rape, the word rape is studiously avoided, Melodia seems curiously immune to the normal trauma of being raped, and by the end of the book she seems to have forgotten all about it. All in all, is a singularly awful representation of rape on every level. It doesn’t make much sense that rape is so rampant in the fantasy world as its described; the use of rape culture rhetoric to justify the rape is presented in a way that seems intended to make the reader sympathize with that misogynistic reasoning; the rape itself is sexualized and written in a way that feels like it’s supposed to be titillating; and the experience and aftermath of the rape and its effects on Melodia’s character are minimized and ignored.

I have some other issues with this book, too, like the sheer stupidity of feudal systems, the cliché religion of the Eight Creators (which is also poorly described throughout the book), the regressive sort of “divine right of kings” politics of characters like Melodia and Jaume, the way that Karyl loses his hand but then grows it back immediately because magic, the inconsistency of Rob’s feelings about the aristocracy, the way that much of the exposition feels like it would be more at home in a D&D campaign setting (Paradise would actually make a pretty cool D&D setting), and so on. But the rape of Melodia is the thing that is a dealbreaker for me. Everything else could have been chalked up to the book being somewhat silly, but it still might have been a fun read. But the level of simmering hatred towards women that pervades this novel isn’t fun for me at all.

As far as I can tell, The Dinosaur Lords is little more than a cynical cash grabbing mash-up specifically and explicitly designed to extract money from the pockets of readers who enjoy a good summer blockbuster. In that sense, I suppose, the book is a success. Much like most summer blockbusters, however, The Dinosaur Lords is terribly light on actual substance and heavy on bullshit. Ultimately, I found it to be deeply unpleasant and alienating. I won’t be reading any more of the series.

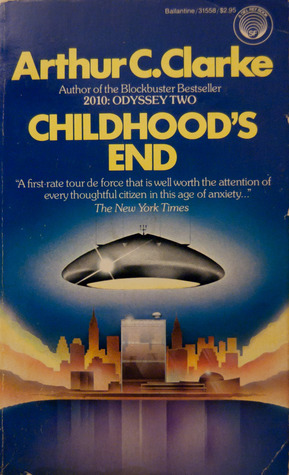

Confession time: I’ve not read very much classic science fiction. As a kid, I was always more into dragons and wizards than space ships and aliens, and as an adult I find I’m just not often interested in reading books that are older than I am. Still, Arthur C. Clarke is one of the greats, Childhood’s End is one of my partner’s favorite books, and it’s

Confession time: I’ve not read very much classic science fiction. As a kid, I was always more into dragons and wizards than space ships and aliens, and as an adult I find I’m just not often interested in reading books that are older than I am. Still, Arthur C. Clarke is one of the greats, Childhood’s End is one of my partner’s favorite books, and it’s

Spindle is a charming little self-published title by Tasmanian author

Spindle is a charming little self-published title by Tasmanian author

Shadowshaper seems to be most often compared to Cassandra Clare’s Mortal Instruments, but it’s a terrible comparison. In fact, there is no comparison to be made that isn’t entirely superficial. Shadowshaper isn’t a flawless piece of work, but it’s not a mess of derivative, hackneyed tropes like the Mortal Instruments series was, either.

Shadowshaper seems to be most often compared to Cassandra Clare’s Mortal Instruments, but it’s a terrible comparison. In fact, there is no comparison to be made that isn’t entirely superficial. Shadowshaper isn’t a flawless piece of work, but it’s not a mess of derivative, hackneyed tropes like the Mortal Instruments series was, either.

I’m not sure that most people would agree with me that The Philosopher Kings is a fun read, but I enjoyed it at least as well as I did its predecessor, The Just City. After the rather abrupt and somewhat shocking ending of the previous book, I couldn’t wait to see what happened next.

I’m not sure that most people would agree with me that The Philosopher Kings is a fun read, but I enjoyed it at least as well as I did its predecessor, The Just City. After the rather abrupt and somewhat shocking ending of the previous book, I couldn’t wait to see what happened next.