Dianna Gunn’s Keeper of the Dawn combines a smartly plotted adventure with a sweetly written romance in a richly imagined fantasy world with plenty of space for more stories if the author chooses to return to it. Unfortunately, it’s all a bit much for a novella-length work. It’s a little overstuffed, and the sequence of events, while well-considered, has a tendency to read like a run-on sentence of “and then this happened and then this happened” and so on; all characters aside from the protagonist are underdeveloped, sometimes to the point of being cardboard; and the denouement could have used good deal more space to breathe. Still, there’s a lot to like about Keeper of the Dawn, and there aren’t so many YA lesbian romances featuring asexual heroines that it’s not still important representation despite its flaws—especially when the biggest flaw is simply that the story could have used another hundred pages or so to address its shortcomings.

Dianna Gunn’s Keeper of the Dawn combines a smartly plotted adventure with a sweetly written romance in a richly imagined fantasy world with plenty of space for more stories if the author chooses to return to it. Unfortunately, it’s all a bit much for a novella-length work. It’s a little overstuffed, and the sequence of events, while well-considered, has a tendency to read like a run-on sentence of “and then this happened and then this happened” and so on; all characters aside from the protagonist are underdeveloped, sometimes to the point of being cardboard; and the denouement could have used good deal more space to breathe. Still, there’s a lot to like about Keeper of the Dawn, and there aren’t so many YA lesbian romances featuring asexual heroines that it’s not still important representation despite its flaws—especially when the biggest flaw is simply that the story could have used another hundred pages or so to address its shortcomings.

While the secondary characters leave quite a bit to be desired, Lai is a mostly well-crafted protagonist with a distinct character arc and notable growth over the course of the book. Her early motivations are a little obscured by the trauma and disappointment of her failure in the trial to become a priestess—it would have been nice to have a deeper understanding of why being a priestess was so important to her and what it was about her mother and grandmother that made her want so much to emulate them. The failure to achieve a lifelong dream works well as the spark to start off Lai’s journey, but there’s too much time spent in the early part of the book dealing with Lai experiencing some mild-to-moderate bullying and struggling with her own resentment over her widower father’s remarriage. It delays the start of the story, and it’s confusing and frustrating when none of this stuff is revisited later or resolved by the end of the book.

That said, once Lai gets going, things improve a great deal. Her decision to run away is impulsive, but it makes sense for her as a character, and the early aimlessness of her journey as she tries to figure out what to do with her life after such a major disappointment is relatable, if not always entirely compelling. Still, even at her lowest point, Lai never falls into the unnecessarily and unpleasantly melodramatic angst that some teen heroines are prone to, and once she discovers the possibility of a future that though different than what she had hoped for herself has the potential to be equally fulfilling, Lai is steadfastly driven to succeed. One particularly admirable trait of Lai’s is that, though she is disappointed by her early failure, she never loses a core of confidence in herself that sustains her through hard times and encourages her to find different ways to achieve her goals of worshiping her goddess and honoring the memories of her mother and grandmother.

The worldbuilding is overall strong, and the idea of sister cultures separated by hundreds of years and miles but still connected through their shared faith is an interesting one. As with many other aspects of the book, it would have been nice to see some of these ideas given more space for development, but fortunately Gunn doesn’t overdo it with details. Necessary exposition about the world is delivered in a competently sparing fashion that never overwhelms the reader with history and backstory. Much of the in-universe history is only learned as Lai learns it on the page and with a minimum of info-dumping. There are a couple of issues with unfortunate implications—primarily with the strict-seeming binary gendering of social roles—and the use of stereotypes as shorthand for cultures and characterization but nothing especially egregious.

Finally, the romance between Lai and Tara is nicely done, without relying too heavily on hackneyed YA romance tropes. At the same time, it’s a romance with a good, comfortable, lived-in quality, without any major relationship-derailing conflicts and with an uncomplicated happy ending. The depiction of Lai’s asexuality seems sensitive, and it’s nice to see a YA-targeted romance that deals so frankly with issues of consent and addresses the potential problems of mismatched sex drives in a healthy and mature way. As a love interest, Tara isn’t extremely exciting, but what she lacks in excitement (which too often means emotional or physical danger in romance) she more than makes up for by being a solid, kind and caring presence, helping Lai to settle into her new community and being a supportive partner to Lai as she undergoes her new set of trials to become a Keeper of the Dawn.

In the end, the biggest shortcoming of Keeper of the Dawn is that it ought to have been longer. There’s a novel-sized story here, especially with the decision to include so much material about Lai’s life before she runs away, and to squeeze it into a novella-sized word count, some areas have to suffer. Another hundred or two hundred pages would have made that decision easier to justify, and it would have offered plenty more space for Lai to work through her issues with her father and stepmother and to explore her feelings about her best friend achieving the goal she had for herself. It also would have allowed the ending of the story to play out less hurriedly, giving more room for Lai to have a return journey instead of just a time-jump and for her to, again, process her feelings about returning to her people and family of origin. The extra length would also have allowed Gunn to give more depth to the secondary characters and add even more worldbuilding flourishes to make her fantasy world come alive.

I didn’t find out about Spindle Fire until about three weeks before its release date, but I was excited when I first read about it. I love fairy tale retellings, and I’d been looking for something that would be a kind of lighter read to help me break out of a reading slump I’ve been in for a couple of weeks. I loved the idea of splitting the story of Sleeping Beauty between two girls, the cover is gorgeous, and the title was getting a decent amount of buzz leading up to its release date. Sadly, Spindle Fire turned out to be a dreary slog of a book. The sisters, Aurora and Isabelle, barely interact and only in the first couple chapters; both Aurora and Isabelle have significant disabilities, but the way they are handled in the text is not great; the romances are at once overwrought and dull; the major “twist” is heavily telegraphed; and the book just, overall, feels choppy and disjointed, with more focus on randomly (and occasionally nonsensically) pretty turns of phrase than on building a coherent plot or cohesive character arcs.

I didn’t find out about Spindle Fire until about three weeks before its release date, but I was excited when I first read about it. I love fairy tale retellings, and I’d been looking for something that would be a kind of lighter read to help me break out of a reading slump I’ve been in for a couple of weeks. I loved the idea of splitting the story of Sleeping Beauty between two girls, the cover is gorgeous, and the title was getting a decent amount of buzz leading up to its release date. Sadly, Spindle Fire turned out to be a dreary slog of a book. The sisters, Aurora and Isabelle, barely interact and only in the first couple chapters; both Aurora and Isabelle have significant disabilities, but the way they are handled in the text is not great; the romances are at once overwrought and dull; the major “twist” is heavily telegraphed; and the book just, overall, feels choppy and disjointed, with more focus on randomly (and occasionally nonsensically) pretty turns of phrase than on building a coherent plot or cohesive character arcs.

I’m not a great reader of urban fantasy and I’ve been (sort of and unsuccessfully) avoiding new series, so I’d skipped Mishell Baker’s Borderline when it came out last year. I cannot tell you how glad I am that I finally read it. It’s a solid story that ticks off a lot of run-of-the-mill urban fantasy boxes while still being clever and original enough to be interesting. Baker takes a smartly naturalistic approach to describing the setting—I’m not a fan of L.A.-set stories in general, but she does a wonderful job of conveying a sort of warts-and-all love for the city without either romanticizing it or dwelling on ugliness. And Millie Roper is a fucking iconic protagonist with a strong and uniquely relatable (for me) narrative voice.

I’m not a great reader of urban fantasy and I’ve been (sort of and unsuccessfully) avoiding new series, so I’d skipped Mishell Baker’s Borderline when it came out last year. I cannot tell you how glad I am that I finally read it. It’s a solid story that ticks off a lot of run-of-the-mill urban fantasy boxes while still being clever and original enough to be interesting. Baker takes a smartly naturalistic approach to describing the setting—I’m not a fan of L.A.-set stories in general, but she does a wonderful job of conveying a sort of warts-and-all love for the city without either romanticizing it or dwelling on ugliness. And Millie Roper is a fucking iconic protagonist with a strong and uniquely relatable (for me) narrative voice.

I read quite a few debut novels and had a cool half dozen on my reading list for the first three months of 2017, but Alex Wells’ Hunger Makes the Wolf was the one I was most looking forward to in the first quarter of this year. I’m happy to say that it did not disappoint. While it may lack some of the great depth and the high level of craft of some of the other debuts I’ve read so far this year, Hunger Makes the Wolf more than makes up for it in other areas. It’s a well-conceived, smartly plotted, enthusiastically fast-paced sci-fi adventure with some cool ideas and a couple of excellent lead characters who’ve got plenty growing still to do in future books.

I read quite a few debut novels and had a cool half dozen on my reading list for the first three months of 2017, but Alex Wells’ Hunger Makes the Wolf was the one I was most looking forward to in the first quarter of this year. I’m happy to say that it did not disappoint. While it may lack some of the great depth and the high level of craft of some of the other debuts I’ve read so far this year, Hunger Makes the Wolf more than makes up for it in other areas. It’s a well-conceived, smartly plotted, enthusiastically fast-paced sci-fi adventure with some cool ideas and a couple of excellent lead characters who’ve got plenty growing still to do in future books.

Amberlough is a brilliantly inventive and gorgeously accomplished first novel for Lara Elena Donnelly, who manages to both test the limits of the fantasy genre and craft a whip smart and timely political thriller at the same time. Comparisons to Cabaret and Le Carré are accurate enough (and certainly intriguing enough for marketing reasons), though I always think we do a disservice to fresh, original work by using such comparisons to shape reader expectations. Amberlough is a fine novel on its own merits, full of bold world building, great characters, big ideas and a thoughtfully bittersweet ending.

Amberlough is a brilliantly inventive and gorgeously accomplished first novel for Lara Elena Donnelly, who manages to both test the limits of the fantasy genre and craft a whip smart and timely political thriller at the same time. Comparisons to Cabaret and Le Carré are accurate enough (and certainly intriguing enough for marketing reasons), though I always think we do a disservice to fresh, original work by using such comparisons to shape reader expectations. Amberlough is a fine novel on its own merits, full of bold world building, great characters, big ideas and a thoughtfully bittersweet ending.

Ada Palmer’s Too Like the Lightning was one of my favorite novels of 2016, and it was certainly among the year’s most unusual and ambitiously daring pieces of speculative fiction. Nevertheless, it felt a little unfinished, and anyone who loved it has no doubt been waiting with bated breath for the sequel that seemed necessary to complete what Too Like the Lightning started. Seven Surrenders is everything I thought/hoped it would be, with a vivid setting, intricate plot, high level philosophical and political ponderings and fascinating cast of characters, a truly worthy sequel to its brilliant predecessor and a powerfully compelling introduction to the conflict to come in the next book in the series.

Ada Palmer’s Too Like the Lightning was one of my favorite novels of 2016, and it was certainly among the year’s most unusual and ambitiously daring pieces of speculative fiction. Nevertheless, it felt a little unfinished, and anyone who loved it has no doubt been waiting with bated breath for the sequel that seemed necessary to complete what Too Like the Lightning started. Seven Surrenders is everything I thought/hoped it would be, with a vivid setting, intricate plot, high level philosophical and political ponderings and fascinating cast of characters, a truly worthy sequel to its brilliant predecessor and a powerfully compelling introduction to the conflict to come in the next book in the series.

So, I read Miranda and Caliban because I love Shakespeare and had never gotten around to reading any of Jacqueline Carey’s other work. I also read two other Tempest-based stories last year (Margaret Atwood’s Hag-Seed and Foz Meadows’ Coral Bones—both excellent) and thought it would be interesting to compare this one to the others. For what it’s worth, Miranda and Caliban is beautifully written, well-structured and readable, but the question I kept coming back to the longer I read it was “Is it necessary?” Sadly, I don’t think it is. I don’t regret having read it, but I also wouldn’t say that it deepened my understanding of The Tempest, Shakespeare or their themes, and what insight it gave me into the author’s understanding of these things didn’t impress.

So, I read Miranda and Caliban because I love Shakespeare and had never gotten around to reading any of Jacqueline Carey’s other work. I also read two other Tempest-based stories last year (Margaret Atwood’s Hag-Seed and Foz Meadows’ Coral Bones—both excellent) and thought it would be interesting to compare this one to the others. For what it’s worth, Miranda and Caliban is beautifully written, well-structured and readable, but the question I kept coming back to the longer I read it was “Is it necessary?” Sadly, I don’t think it is. I don’t regret having read it, but I also wouldn’t say that it deepened my understanding of The Tempest, Shakespeare or their themes, and what insight it gave me into the author’s understanding of these things didn’t impress.

Thoraiya Dyer’s Crossroads of Canopy was one of my most anticipated debut novels of 2017, and I’m pleased to report that it did not disappoint. Crossroads is a truly tremendous book, full of fantastically original worldbuilding, fascinating mythology, and a cast of compelling characters led by one of my favorite fantasy heroines in a very long time. It’s a gorgeously magical and delightfully challenging novel that only gets lusher and more incredible the longer you read it.

Thoraiya Dyer’s Crossroads of Canopy was one of my most anticipated debut novels of 2017, and I’m pleased to report that it did not disappoint. Crossroads is a truly tremendous book, full of fantastically original worldbuilding, fascinating mythology, and a cast of compelling characters led by one of my favorite fantasy heroines in a very long time. It’s a gorgeously magical and delightfully challenging novel that only gets lusher and more incredible the longer you read it.

Lady Castle is, for me, the first must-read comic of 2017. I don’t read a ton of comics, to be honest, and I’m pretty choosy about what I spend my time and money on, usually going for limited projects with women writers and artists and steering clear of superhero stuff. I’ve also, in recent years begun avoiding any of the trite ’90s-esque girl power stuff being put out by a certain breed of right on self-identified feminist white dudes, which has sadly left me with a medieval fantasy adventure comic-shaped hole in my life. Long story short, Lady Castle is exactly the comic that I’ve been yearning for over the last several years. It’s perfect and I love it and you should be reading it right now if you haven’t already.

Lady Castle is, for me, the first must-read comic of 2017. I don’t read a ton of comics, to be honest, and I’m pretty choosy about what I spend my time and money on, usually going for limited projects with women writers and artists and steering clear of superhero stuff. I’ve also, in recent years begun avoiding any of the trite ’90s-esque girl power stuff being put out by a certain breed of right on self-identified feminist white dudes, which has sadly left me with a medieval fantasy adventure comic-shaped hole in my life. Long story short, Lady Castle is exactly the comic that I’ve been yearning for over the last several years. It’s perfect and I love it and you should be reading it right now if you haven’t already.

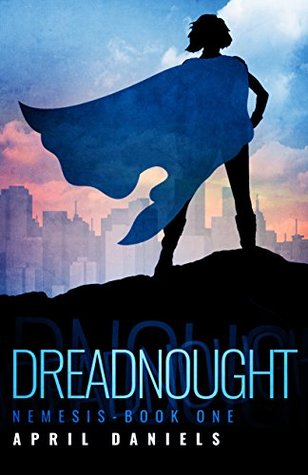

I love that Dreadnought is a thing that exists in the world more than I actually enjoyed reading the book, though I did rather like it. It’s being marketed as great for fans of last year’s The Heroine Complex and Not Your Sidekick, and both of those were titles that I just never did quite manage to get around to reading, mostly because I’m not super into super hero stories. Like these other books, Dreadnought centers around an unconventional protagonist, in this case a fifteen-year-old closeted trans girl named Danny who has to quickly come to terms with her identity when she is unexpectedly gifted with both superpowers and the body she’s always known she should have. Danny is a smart, plucky, relatable heroine who I expect will be an education for some readers and a much-needed bit of representation for others. Nonetheless, Dreadnought is a book that I read with the constant awareness that it wasn’t for me. Danny’s story of self-discovery and actualization is one that will be compelling for any reader, but I imagine it will resonate most deeply with readers who share more of Danny’s experiences as a trans girl.

I love that Dreadnought is a thing that exists in the world more than I actually enjoyed reading the book, though I did rather like it. It’s being marketed as great for fans of last year’s The Heroine Complex and Not Your Sidekick, and both of those were titles that I just never did quite manage to get around to reading, mostly because I’m not super into super hero stories. Like these other books, Dreadnought centers around an unconventional protagonist, in this case a fifteen-year-old closeted trans girl named Danny who has to quickly come to terms with her identity when she is unexpectedly gifted with both superpowers and the body she’s always known she should have. Danny is a smart, plucky, relatable heroine who I expect will be an education for some readers and a much-needed bit of representation for others. Nonetheless, Dreadnought is a book that I read with the constant awareness that it wasn’t for me. Danny’s story of self-discovery and actualization is one that will be compelling for any reader, but I imagine it will resonate most deeply with readers who share more of Danny’s experiences as a trans girl.