Whew! Truthwitch is an absolutely exhausting, if exhilarating, read. There’s an enormous amount of stuff going on in this book, and I kind of loved it, but the problem with doing lots of things in a novel is that it’s only seldom that they’re all done well. Like many other ambitious and complex works, especially those intended for a YA audience, Truthwitch is a bit of a mixed bag.

Whew! Truthwitch is an absolutely exhausting, if exhilarating, read. There’s an enormous amount of stuff going on in this book, and I kind of loved it, but the problem with doing lots of things in a novel is that it’s only seldom that they’re all done well. Like many other ambitious and complex works, especially those intended for a YA audience, Truthwitch is a bit of a mixed bag.

The biggest problem with Truthwitch is that, while a ton of stuff happens, nothing is resolved and not all of the things that happen seem to belong in the same story with each other. Some parts feel almost entirely disconnected from the rest, while other parts are both too obviously connected with each other and made to feel much more mysterious than they actually are.

The book opens with main characters Safiya and Iseult in the middle of a “heist,” though it’s never particularly clear what they’re up to, how they planned to get away with it, or why this was how Susan Dennard decided to start the story. It could be intended to establish the girls’ “normal” state of affairs, but it’s made very clear later on that this was something that they did infrequently, as both of them have legit positions in the city they live in that would prevent them from really engaging in a life of crime—not to mention the ways their choices are constricted by their social positions. It’s a strange opening that—even more so in hindsight—feels like the beginning of a very different book than what we’re actually given.

Once you get past the unfortunately confusing and unnecessarily cold open, though, Truthwitch is a fast-paced, enjoyable read. It’s still somewhat scattered at times, with a couple of lengthy diversions into subplots that I’m sure will come to fruition later in the series, but the majority of the book is forward motion. By the final quarter, it veritably hurtles towards a conclusion that is equal parts devastating (in a good way), aggravating, and altogether too neat after the chaotic middle section of the book. This is highlighted by having a final chapter dedicated to wrapping up each character’s story in a few paragraphs to prepare the reader for the next book. This seems to be a common trend in YA series, and I hate it. It’s just too much like handholding, and it puts me in mind of the stilted, at-least-half-redundant fashion in which eighth graders write conclusions to essays.

The other major issue I have with this book is a world-building complaint. While the Witchlands is a big, beautiful, complex fantasy world, the details of its magic system can be frustratingly opaque at times. It’s a great idea, and I loved all the different types of magic, but there are several concepts that are woefully underdeveloped and a couple that are just plain ill-conceived. The worst offenses on this score are Safi and Iseult’s powers, which are both poorly defined and not utilized very smartly in the narrative.

Iseult’s magic as a Threadwitch seems useful, but it’s obvious early on that her abilities are non-normative. It’s also just not really that clear what exactly Threadwitch’s do. Although Iseult’s mother seems to have an important place in their Nomatsi community, it’s never actually explained what her role is or how the Threadwitch magic works. Instead, there’s a lot of sort of mystical explanations that seem at odds with the utilitarian descriptions we get when Iseult actually uses her powers.

Meanwhile, Safi’s magic as a Truthwitch is supposedly extremely rare and ridiculously powerful, but there’s nothing in the narrative to confirm that this is truly the case. Again, there are some descriptions of her using her magic that make is seem extremely useful, but it doesn’t seem to affect Safi’s day to day life that much. Especially when it’s revealed—and relatively early in the book—that Safi’s witchery may not be as accurate or powerful as everyone seems to think, I was left feeling that there’s a good deal of much ado about nothing going on. Indeed, Safi’s magic seems redundant and second-rate when Wordwitches exist; certainly, it doesn’t seem to be powerful enough to be worth starting a world war over, though that is exactly what is happening by the end of the book.

That said, the way that Dennard describes and utilizes the magic of the book’s secondary characters is really well-done. Wordwitches, Glamourwitches, and Windwitches drift in and out of the narrative doing really interesting stuff with their magics, which are shown rather than told about. The Bloodwitch, Aeduan, has his abilities described wonderfully—much more what I would expect of a very rare and powerful magic—and again we are shown how his magic works and the way it fits into the story Dennard is telling. I expect that Safi and Iseult’s magics will play a much larger role in future books, but there’s a coyness to the way they’re used in Truthwitch that I found highly unpleasant, largely because of the way in which it contrasts with the much better fashion in which Dennard shows us literally everyone else’s magic.

The greatest strength of Truthwitch, on the other hand, is its focus on exploring friendship and the families that people choose as opposed to those we’re born into. Safi and Iseult’s relationship is the strongest one in the novel, and no matter what else happens to the two girls, they prioritize their love for each other over nearly everything else. With so many other YA books having a heavier focus on romance, it’s delightfully refreshing to read something where everything revolves around the friendship and love between two young women. At the same time, both Safi and Iseult are distinct individuals with concerns, plans, hopes, and dreams of their own. Though their destinies may be intertwined, they are never subsumed in each other, and their personalities are complementary rather than particularly similar to each other.

That’s not to say that there isn’t any romance, of course, and I found myself rather enjoying Merik and Safi’s hate-to-love journey, though it’s not covering any new ground in the genre. It’s pedestrian, but in a way that is comfortingly familiar. It also helps that it’s not given so much page time that it distracts from other things. Additionally, Merik’s friendship with Kullen is well-portrayed as a parallel to Safi’s friendship with Iseult, so there’s much more than just a romantic subplot going on. Speaking of romance, though, I’m much more interested in whatever is going on between Iseult and Aeduan. Yeah, he’s a terrifying Bloodwitch who is hunting the girls across the world to probably kill them, but there are some sparks there (#iamtrash).

All in all, Truthwitch is a solidly entertaining read and a strong start to an interesting new series. It’s very reminiscent of Sarah J. Maas’s Throne of Glass series, and I’m loving this kind of sword and sorcery trend in YA fiction. While Truthwitch isn’t perfect, none of its flaws are fatal ones, and all are forgivable. I can’t wait to see what happens in the Witchlands next.

I can’t believe I waited so long to read this comic. Like, I’m truly appalled at myself, and now that I’ve read the first five issues, I can’t even remember why I hadn’t been that interested. Bitch Planet is a gorgeously drawn, tightly plotted feminist masterpiece that should be required reading for women everywhere. It’s also brutal and heartwrenching and more than a little uncomfortably close to the truth of many women’s experiences.

I can’t believe I waited so long to read this comic. Like, I’m truly appalled at myself, and now that I’ve read the first five issues, I can’t even remember why I hadn’t been that interested. Bitch Planet is a gorgeously drawn, tightly plotted feminist masterpiece that should be required reading for women everywhere. It’s also brutal and heartwrenching and more than a little uncomfortably close to the truth of many women’s experiences.

All the Birds in the Sky, on its surface, is a story about two weirdos who come of age and fall in love during an apocalypse. It’s a story infused with magic, from the first time we see Patricia talk to a bird, and it’s a story about bad timing, from the moment Laurence makes his first two-second time machine. It’s a comedy of errors about the end of the world, and it’s one of the most wonderful things I’ve ever read. I’m only a little disappointed to have read it so early in the year. I feel about All the Birds in the Sky the way I felt about N.K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season (which this novel is absolutely nothing like) last year; I just know, deep down, that nothing else I read in 2016 is going to top it.

All the Birds in the Sky, on its surface, is a story about two weirdos who come of age and fall in love during an apocalypse. It’s a story infused with magic, from the first time we see Patricia talk to a bird, and it’s a story about bad timing, from the moment Laurence makes his first two-second time machine. It’s a comedy of errors about the end of the world, and it’s one of the most wonderful things I’ve ever read. I’m only a little disappointed to have read it so early in the year. I feel about All the Birds in the Sky the way I felt about N.K. Jemisin’s The Fifth Season (which this novel is absolutely nothing like) last year; I just know, deep down, that nothing else I read in 2016 is going to top it.

As is often the case with popular fairy tales, there’s very little new story to be wrung out of “Beauty and the Beast” these days, so I was a little skeptical of Bryony and Roses. Even after reading T. Kingfisher’s (a pen name of Ursula Vernon) Toad Words and Other Stories, which is full of superb fairy tale reimaginings, I was unsure if there was anything she could do to freshen up such an old and well-worn story path. An opening note that admitted an enormous debt to Robin McKinley, whose Rose Daughter is perhaps the definitive feminist “Beauty and the Beast,” was frankly more concerning than reassuring. I ought not have worried so much. Just like in her earlier fairy tale work, Vernon-as-Kingfisher does an incredible job of exploring and revitalizing ancient material, infusing it with a bright, modern, thoroughly feminist (and unequivocally delightful) sensibility.

As is often the case with popular fairy tales, there’s very little new story to be wrung out of “Beauty and the Beast” these days, so I was a little skeptical of Bryony and Roses. Even after reading T. Kingfisher’s (a pen name of Ursula Vernon) Toad Words and Other Stories, which is full of superb fairy tale reimaginings, I was unsure if there was anything she could do to freshen up such an old and well-worn story path. An opening note that admitted an enormous debt to Robin McKinley, whose Rose Daughter is perhaps the definitive feminist “Beauty and the Beast,” was frankly more concerning than reassuring. I ought not have worried so much. Just like in her earlier fairy tale work, Vernon-as-Kingfisher does an incredible job of exploring and revitalizing ancient material, infusing it with a bright, modern, thoroughly feminist (and unequivocally delightful) sensibility.

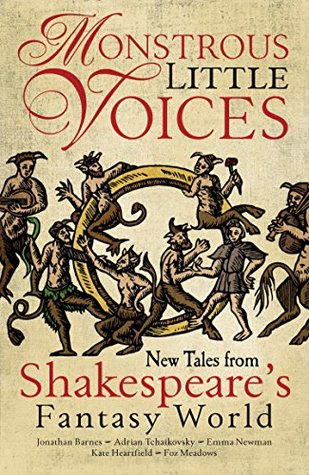

Monstrous Little Voices is a collection of five short novellas that take place within a fantasy world based upon the works of William Shakespeare, and it’s about 80% brilliant, which is pretty good for an anthology. There’s something of an overarching storyline connecting the stories, in addition to common themes and motifs, and this is nicely executed without making the stories feel totally linear or requiring them to be read in order. At the same time, each one also stands alone quite well.

Monstrous Little Voices is a collection of five short novellas that take place within a fantasy world based upon the works of William Shakespeare, and it’s about 80% brilliant, which is pretty good for an anthology. There’s something of an overarching storyline connecting the stories, in addition to common themes and motifs, and this is nicely executed without making the stories feel totally linear or requiring them to be read in order. At the same time, each one also stands alone quite well.

Whew! Truthwitch is an absolutely exhausting, if exhilarating, read. There’s an enormous amount of stuff going on in this book, and I kind of loved it, but the problem with doing lots of things in a novel is that it’s only seldom that they’re all done well. Like many other ambitious and complex works, especially those intended for a YA audience, Truthwitch is a bit of a mixed bag.

Whew! Truthwitch is an absolutely exhausting, if exhilarating, read. There’s an enormous amount of stuff going on in this book, and I kind of loved it, but the problem with doing lots of things in a novel is that it’s only seldom that they’re all done well. Like many other ambitious and complex works, especially those intended for a YA audience, Truthwitch is a bit of a mixed bag.

I expected to love The Drowning Eyes, but I’m sad to say I only liked it. The gorgeous cover art and the book’s description had me very excited about it, but it just wasn’t quite what I expected.

I expected to love The Drowning Eyes, but I’m sad to say I only liked it. The gorgeous cover art and the book’s description had me very excited about it, but it just wasn’t quite what I expected.

I received a free advance copy of this title from the publisher via NetGalley.

I received a free advance copy of this title from the publisher via NetGalley.

I received a free advance copy of this title from the publisher via NetGalley.

I received a free advance copy of this title from the publisher via NetGalley.

Future Visions had me at Ann Leckie (also at “free” because who passes up free stories?), but it turns out that Microsoft’s first foray into sci-fi publishing is actually a solidly good collection of work. I honestly wasn’t at all certain that it would be, and, worse, I was more than a little concerned that it would end up being little more than an extended, fictionalized advertisement for Microsoft products. Instead, it’s a well-produced anthology of hard sci-fi that ranges from very recognizable speculation about the near-future to space opera.

Future Visions had me at Ann Leckie (also at “free” because who passes up free stories?), but it turns out that Microsoft’s first foray into sci-fi publishing is actually a solidly good collection of work. I honestly wasn’t at all certain that it would be, and, worse, I was more than a little concerned that it would end up being little more than an extended, fictionalized advertisement for Microsoft products. Instead, it’s a well-produced anthology of hard sci-fi that ranges from very recognizable speculation about the near-future to space opera.